The Memorial Congregational Church sits by itself on a December afternoon on a Mountrail County prairie where it was moved in 1953.

In the fall of 2009, the prairie grasses surrounded the solid church building that once stood along the Missouri River.

You know there are stories behind those abandoned church buildings — such as this one. What’s the story there? Take a trip on Highway 1804 to step back in time.

For me, it was easy to ignore the abandoned prairie church building along Highway 1804 as I headed up north to Parshall, North Dakota. But once I stopped to check it out, I uncovered layers of monumental history. Now, I stop often to step into the history.

Charles L. Hall, born in England in 1847 moved to New York and became an architect, working in a local mission until he moved to the Dakota Territory.

The story goes back to 1871 when the Dakota Territory was organized and an architect from England worked in a New York mission. Charles Hall felt the call to minister to the same people who had ministered to Lewis and Clark 67 years earlier, the Mandans.

The same year that the 7th Cavalry marched to Little Big Horn, Charles Hall floated the Missouri River for two weeks up river to get to his destination. He got off a steamboat armed not with a rifle but with the “Sword of the Lord.” He landed at Like-a-Fishhook Village where he met with a community of Mandan and Hidatsa people. (The village is under Lake Sakakawea, now, southwest of White Shield, ND.)

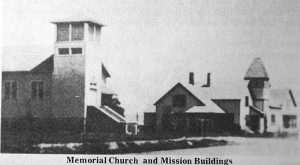

What Custer couldn’t do with a rifle, Hall did with the Gospel. Hall built a school, a community building, successfully lobbied for a bridge (Four Bears Bridge) to cross the Missouri and eventually built this church building at Elbowoods, North Dakota. It’s the only physical reminder of a work he began about 140 years ago in western North Dakota. It was a long challenge to get it built– yet it still stands today.

Hall labored among the area’s farmers, ranchers and other residents, both white and Native-American for 10 years before the first man converted to the Christian faith.

Hall labored among the area’s farmers, ranchers and other residents, both white and Native-American for 10 years before the first man converted to the Christian faith.

Trust was earned slowly, but once earned, it became invaluable. Later both whites and enrolled tribal members met together to worship and socialize.

After 45 years feeding, teaching, healing whites and Natives, the locals followed the architect-missionary’s plans to build this solid building next to the mission and school he started at Elbowoods.

When the building was dedicated, crowds came from as far as 30 to 50 miles over rugged Badlands trails and barely passable roads to join in the dedication. Dignitaries from Bismarck, Minot and New York also came to the dedication.

In his years on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation, Hall helped the members of the Three Affiliated Tribes rise above the limits placed on them by the dictatorial federal government Indian Agency at Elbowoods. The Indian Agency was so harsh, Hall later testified, that the Indian Agent required tribal members to stop and bow their head when he walked by. If they received visitors, the visitor would first have to meet with the Indian Agent before going to meet the family or friends they came to see.

That kind of government attitude that could be part of the reason why local residents living in poverty would pay $10 a month to have their children schooled, fed and cared for by Hall’s mission school instead of going to the free government school. Wages at that time were about 60 cents a day – if someone could find paying work. The Mandan were an agricultural people; they tilled the river bottom along the Missouri River and grew corn, squash, pumpkin, sunflower and tobacco. To afford the school with its training, food, health provisions and social network families took their produce by horse-drawn wagon to sell in towns such as Minot, 60-miles north. They used their money to support the mission, its school, church and community programs.

The nearby cemetery is still used as a final resting place for tribal members. Until 2014, a woven wire fence surrounded the cemetery.

The Elbowoods Congregational Mission church building was dedicated to Charles Hall’s second wife, Susan Webb Hall. He had lost at least two children and his first wife to the tireless work of reaching local people with improved diet, health and education. The church people were both white and native; racial distinctions were erased at the Cross. Together, they built the building by themselves, by hand. They didn’t borrow a penny to build it. It cost them $5,500, with $3,500 coming from their own donations, and another $2,000 donated by friends of Charles Hall.

When the federal government flooded out the people who lived along the Missouri River and the towns such as Elbowoods, hundreds of families were forced to move out of their homes. A hospital, a school and many businesses were flooded. Locals moved five church buildings out of the valley, including the Susan Webb Hall Memorial Church building.

Starting on a Friday night, as the flood waters moved up in to town, and up on to the foundation of the building, local farmers and ranchers worked non-stop to lift the building from its original footings at Elbowoods. By the time they got it up a bit of a hill, the flood was already taking over the original site. Their work was not done until they moved the building nine miles north near the communities of Lucky Mound, Parshall and White Shield.

Click on the image to see it full screen and to see the love note to Grandpa.

Today, the building is more than 90 years old and stands alone on the prairie where it was moved during the man-made flood. When it was moved to its current site, neighbors saw it move in. They said it seemed to them the church was all lit up. A story on the relocated church quoted the neighbors who said “It gave them a queer feeling as they had never lived near a church before.”

Today, the building is more than 90 years old and stands alone on the prairie where it was moved during the man-made flood. When it was moved to its current site, neighbors saw it move in. They said it seemed to them the church was all lit up. A story on the relocated church quoted the neighbors who said “It gave them a queer feeling as they had never lived near a church before.”

No windows or doors remain on the old structure, though it appears to be solid in its old age. No furnishings remain inside, no furniture or other features, just a love note to a grandfather.

It’s a sacred place and vandals have not left graffiti or other degrading elements. The bell tower is as empty as the rest of the building, though it once held a donated bell that called people to worship through out the early Missouri River Valley.

It’s a sacred place and vandals have not left graffiti or other degrading elements. The bell tower is as empty as the rest of the building, though it once held a donated bell that called people to worship through out the early Missouri River Valley.

Autumn of 2009, the church stands isolated and preserved. (Click on the image to see it full screen.)

I don’t know about a queer feeling, but it certainly is inspiring to know the history behind the building, a part of North Dakota history that few know. Charles Hall left an account of the work in his collection of documents assembled in the book 100 Years at Ft. Berthold, 1876 to 1976. I’m thankful to one of the tribal elders, Mary Bateman who lent me her copy. What would you suggest as a way to make the historic landmark more famous?

(you can click on any of the images to see them full screen)

#ndlegendary

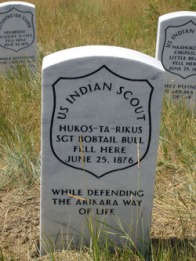

Go back to the first Hidatsa scout, Sakakawea (Hidatsa pronunciation suh-CAG-a-wee-uh). She and her husband Charbonneau helped the Corps of Discovery find its way west and back again.

Go back to the first Hidatsa scout, Sakakawea (Hidatsa pronunciation suh-CAG-a-wee-uh). She and her husband Charbonneau helped the Corps of Discovery find its way west and back again.

Have you taken the scenic drive past Garrison, up to Parshall on 1804? Did you see the Old Scouts Cemetery?

Have you taken the scenic drive past Garrison, up to Parshall on 1804? Did you see the Old Scouts Cemetery?